Little Muddy Universe

I live on the edge of a muddy estuary.

The slow-moving inundations and rhythmic oscillations of this vast other-worldly Neptunian amphitheatre have tilted my consciousness over time towards a fascination with fluid dynamism. Twice daily, a long-slow yawn of water trickles across the 2-kilometre stretch of mud between high and low tide, until the bay is fully bloated, and the mangroves are waist high in ocean. As the slowing waves reach the soft-limestone rock forms along the erratic edge of the rain forest, they create orbits of overlapping ripples in all directions. The slow retreat of the outgoing tide, has a back and forth oscillation at its edge, as waves in reverse, retreat over the mud towards the harbour. Rings of birds strut and poke along the shifting tidal fringe .

A natural amphitheatre of not only sound - waves chased by wind, birds cawing as they circle over sucking mud, popping mangrove pods - an amplifier of beauty and chaos in never-ending symbiotic communion.

This muddy estuary, pragmatically named Little Muddy Creek, inspired my PhD on Liquid Urbanism and every creative idea since.

Little Muddy

For my PhD I researched “liquid themes” in film, urbanism, architecture, art, and landscape forms.

I discovered the language of dynamic systems. I watched ripple effects overlay for hours on ends, and tried to calculate the algorithms of these circular wave forms. I read about black holes and watched water disappear down the sink or the bath. I researched suction. And magnetism. And flow forms. I read about liquid perception and watched early French cinema by Jean Vigo and Gremilion that floated watery themes as counter narratives to the fascist politics of early 20th century Europe. At the same time I read urban theory as cities were being redefined by transience and movement streams, rather than assemblages of built form. I also observed a surge of innovation around urban waterspaces.

I visited a 2000 year old irrigation project in China, an exemplar of ancient Chinese water engineering that is still in use today. I visited water gardens and paddy fields in Thailand and Cambodia. I photographed the canals of Paris. I watched the massive tidal shift of the Garonne in Bordeaux where the ocean met the fresh water downstream force, creating fields of whirlpools across a tempestuous surface.

I came to the understanding that water is a highly communicating medium, a continuous living demonstration of universal dynamism, but also that its dynamism generates magnetism. I pondered that if attraction is indeed a cohesive force in our universe, then urban waterscapes with their own dynamical theatrics may also act like attractors and contribute towards cohesive social environments in cities.

I read Henry Bergson, Gilles Deleuze, Phillip Ball, Viktor Schauberger, Brian McGrath, Theodor Schwenk, Lars Spuybroek, amongst many others.

I researched strange attractors in the beautiful library at the top of the Musee d’Architecture in Paris, and I wondered how cities dissolve and reform around new social streamings. What could cities learn about resilience from ancient galaxies. How did galaxies maintain coherence across multitudes of cosmic bodies?

My research experiences were profound and yet to draw conclusions within the required academic format was difficult because water itself is by nature always elusive, enigmatic and shapeshifting. I wrote, and wrote, and wrote, yet rarely felt like I arrived anywhere, except to be reabsorbed as the witness of yet another brilliant iteration in a fractal matrix , another universe in a universe of infinite dynamic patterning. I was mesmerised into incoherence to be truthful. Out classed by my research topic by quantum degrees.

An image of a strange attractor generated by an algorithm in Processing from my PhD. The image describes how galaxies are organised by energetic super highways called Strange Attractors. Copyright Jaqs Clarke

And so in the haze of post-PhD life, when a friend suggested I make a children’s book, I entertained the idea because studying water has revealed to me the workings of the universe in glimpses, even momentarily. Yet I wanted to generate something simple and actually more heartfelt. The Book of Water Magic is my PhD squeezed, bent and inverted into a completely novel expression. It took forever. The process of going from what is credible to an academic brain, to what is magical to a young child’s was like moving from the equator to the south pole. Moving from the serious, rational and considered to the whimsical and playful, I had to unschool my brain. I had to stop rowing across a very wide river with only a teaspoon. I had to find the universal in one singular fine pencil mark. How to be that light?

“At ponds, rivers and freshwater springs, lives a Sprite who loves to sing, while playing in sparkling dew, but should she get a fright, soon disappears out of sight.”

From The Book of Water Magic

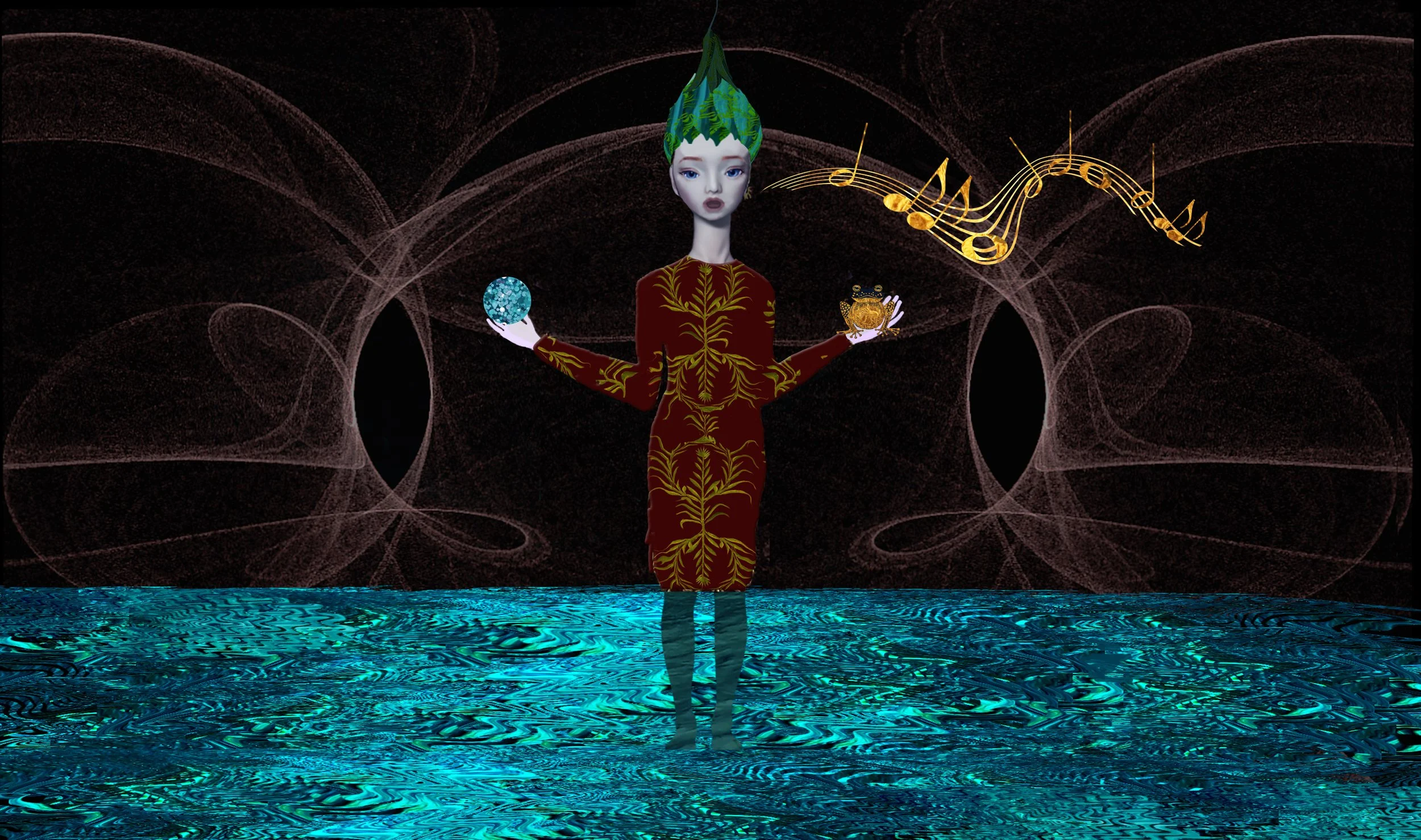

The strange attractor doubles to make a cave-like stage in The Book of Water Magic.

Copyright Jaqs Clarke

The Book of Water Magic is somewhere between Thumbelina, that water nymph of my childhood reading who floated on lotus leaves, and Masaru Emoto’s photos of water’s subtle responses to human thought. The boat on the cover has a Danish bow and some Celtic spiral forms from my own ancestral lines, but also resembles a Maori waka or canoe. The water sprite is taken from European mythology, like a leprechaun, but also could be Patupairehe, the pale fairy people of New Zealand. The wriggling stream is an ode to the freshwater channel of my little muddy universe. (See below) Inside there are billowing Turneresque cloud forms, Japanese wave patterns, anime moments, diagrams, poetry, aurora, echos, Neptunian surfers, dissolvings, bopping H2O molecules, shimmerings etc. It contains dynamic systems science but also art mashups. It’s a kind of steampunk fairy watery underworld, the place of magic water helpers – and my hope that everyone wants to be one.

Hoping it will make a splash.

Jaqs Clarke has a PhD in the Philosophy of Architecture from the University of Auckland, School of Architecture and Planning, New Zealand 2013. She was nominated for the Vice Chancellor’s Prize for Best Doctoral Thesis, 2013.

The fresh water channel that weaves down through the mangroves and then through the oyster banks (left) where herons, ducks, kingfishers, seagulls, terns, oyster catchers, spoonbills and even Kotuku nest and feed.